New EcoScope research helps advance use of EBFM ecosystem models for sustainable fishery management

Researchers of the EU-funded EcoScope project published a study on “Using ecosystem models to inform ecosystem-based fisheries management in Europe: a review of the policy landscape and related stakeholder needs” in October 2023 in the academic journal Frontiers in Marine Science.

Due to the impacts of unsustainable fishing on a wide range of species, habitants, human populations and entire ecosystems, compacted by models focusing narrowly on single fish species, neglecting all other wider impacts, a “pressing need” emerged for ecosystem-based fisheries management (EBFM), which is now required by various EU and global policies, the EcoScope research team noted.

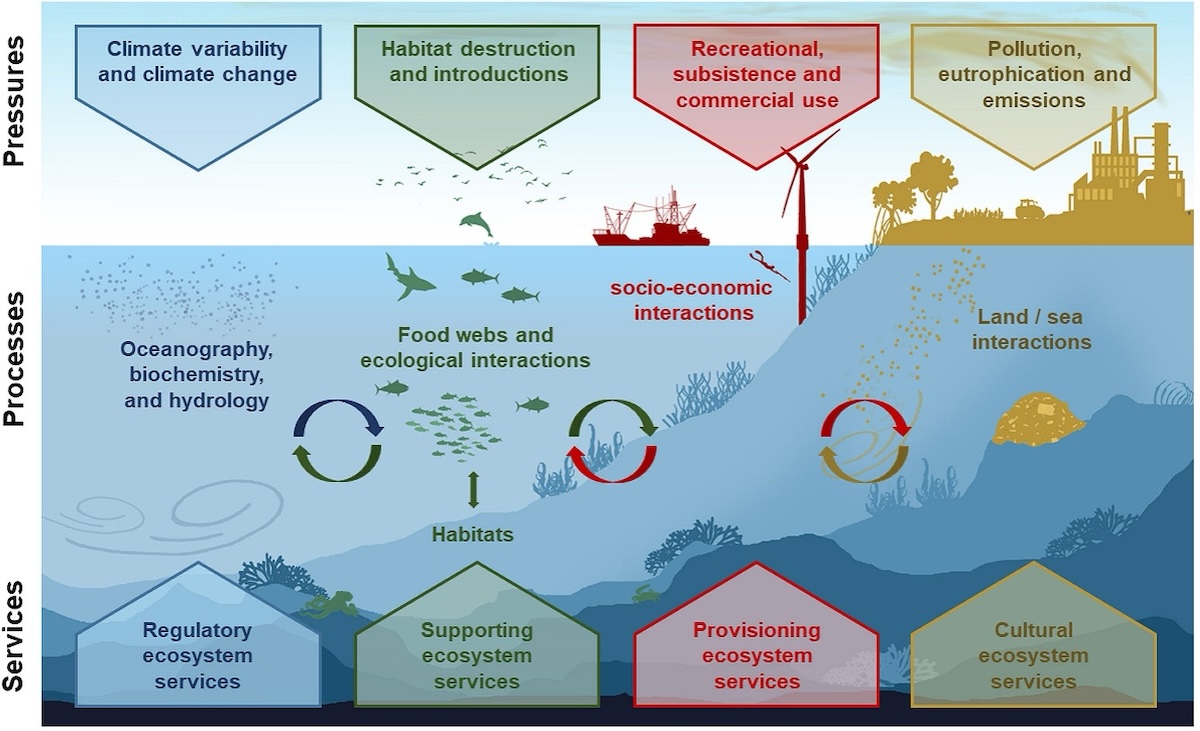

The range of interconnected pressures, processes and ecosystem services that complex spatial-temporal marine ecosystem models may consider. Image from Steenbeek et al., 2021a (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0).

“The aim of this paper is to distil critical policy-related needs relevant to EBFM, that can be addressed using ecosystem modelling,” they said. The research therefore provided an overview of European and global policy commitments requiring EBFM in Europe, as well as an assessment of relevant stakeholder needs.

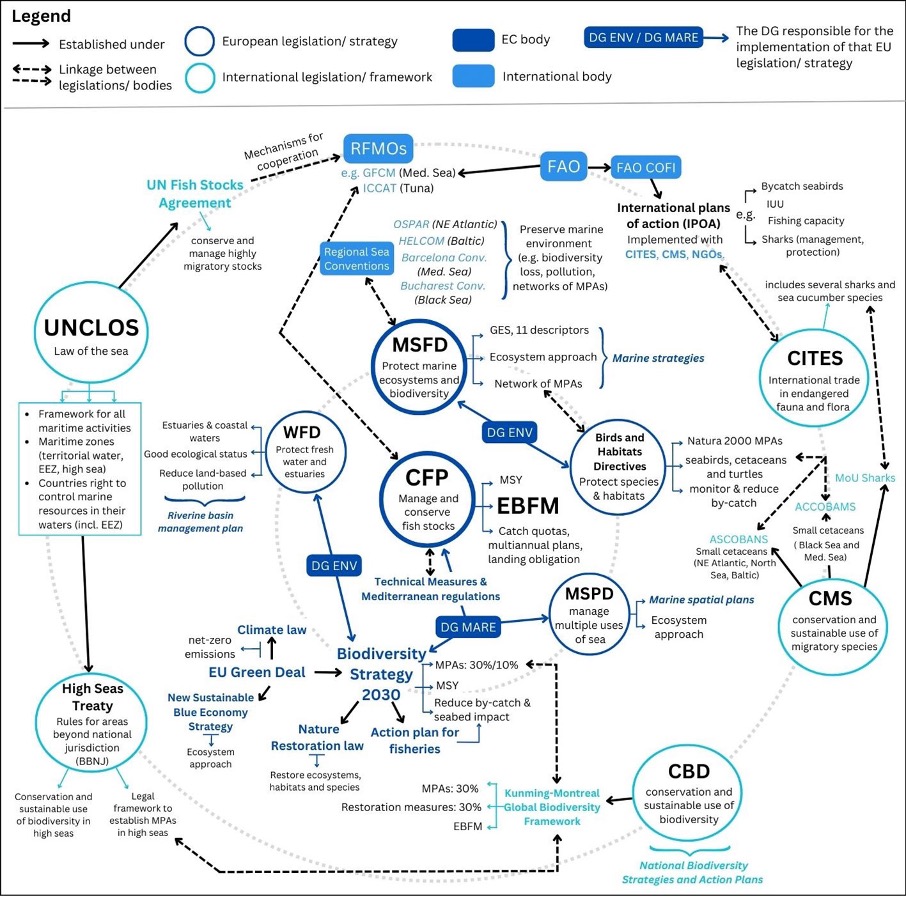

EBFM policy landscape, including interlinkages and main objectives of legislations, conventions and strategies relevant to EBFM in the EU. The CFP is depicted in the middle as the most relevant European legislation, surrounded by other European environmental directives and strategies (with the MSFD highlighted in bold because it is the second most relevant legislation for implementing EBFM in the EU). The outer circle represents international conventions and bodies, which are directly or indirectly linked to the implementation of EBFM in Europe.

“One of the principle aims of the EcoScope project is to use ecosystem modelling as a tool to assist in the implementation of EBFM and, within the ecosystem modelling framework and in parallel with research questions, to co-design the modelling scenarios with the relevant stakeholders in order to address policy questions,”the researchers explained, noting that a policy-focused approach is generally lacking in otherwise potentially relevant modelling.

“Despite clear capability and progress in marine ecosystem modelling, many models are designed to answer scientific, not policy question, which hinders uptake in policy. Ecosystem models that are designed to address policy questions need to be linked to policy goals and targets. In order to inform EBFM, it is therefore important to understand the relevant policy landscape and the needs of related stakeholders,” they said.

Research team members noted that there are two main stakeholder target audiences: those who want easy to understand summary results, such as politicians, fishers, and other practical end-users of the data, and those who need more details and the possibility to independently dig further and deepen their understanding of the background, such as advisory bodies and advocacy groups. “Therefore, it is important to know the target audience of your models,” they commented.

Additionally, EBFM requires more complex approaches and modeling methods based on the entire ecosystem, the EcoScope researchers noted, taking into account such elements as the human socio-ecologic system and climate change as well.

“In practice, implementation of EBFM requires interdisciplinarity, including applied science, modelling, and analysis of diverse streams of information, making it difficult to implement,” the EcoScope team pointed out.

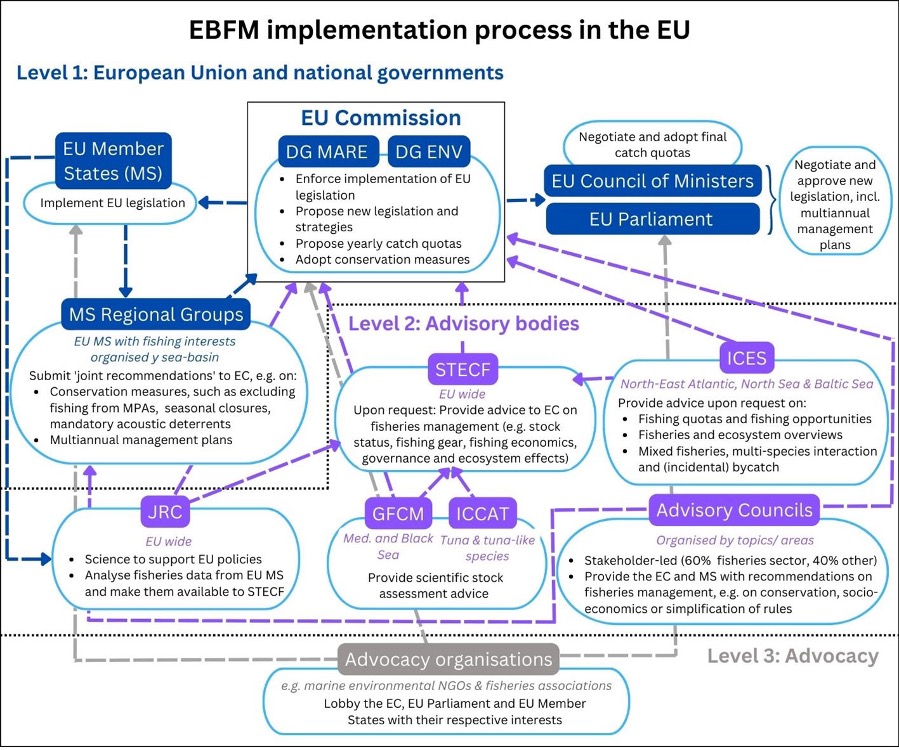

EBFM implementation process in the EU, including the decision-making process and the influencing power of the different bodies.

The team concluded that involving stakeholders throughout the scenario development and modelling process, as well as presenting the results in consultation with the stakeholders – and ensuring that the results and limitations of the model are presented understandably to them – are crucial to ensuring that the model results are relevant and have an impact on policy implementation.

Increasing the clarity and understandability of the model results for decision-making and policy can be done by focusing on trends rather than specific values, presenting ranges of values instead of final numbers, and grading results in terms of certainty instead of uncertainty, the researchers said in their recommendations.

“Uptake of ecosystem models in policy requires that models address specific policy needs […] and deliver outputs that are easily interpreted by policy makers and can be adjusted to the management capabilities and legislation while communicating the degree of certainty (or uncertainty) in the model projections”, they said, noting that a lack of trust in such models has to be overcome, alongside other barriers.

The priority EBFM topics for stakeholders included the effects of climate change, bycatch, protected areas and fisheries in restricted areas, and reducing the impacts of trawling, the researchers noted.

Specific policy requirement areas requiring ecosystem modelling and therefore necessitating EBFM include: maintaining fishing pressure at maximum sustainable yield (MSY) or less and applying MSY to mixed fisheries; identifying areas of highest incidental bycatch and assessing effects on populations and ecosystems; finding the most suitable areas for expanding Marine Protected Areas to cover 30% of EU waters and designate 10% as strictly protected; protecting sensitive/endangered species by defining maximum allowable mortality rates and finding key areas to protect important life-stages; reducing seabed impacts; assessing the effects of climate change; ensuring natural ecosystem processes are not disturbed; informing marine spatial planning; having biodiversity indicators; and, “very importantly”, having long-term predictions of management scenarios, team members said.

The EcoScope research was carried out by Ana Rodrigues-Perez of the European Marine Board, Athanassios Tsikliras of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki School of Biology’s Laboratory of Ichthyology, Gideon Gal of the Israel Oceanographic and Limnological Research Kinneret Limnological Laboratory, Jeroen Steenbeek of the Ecopath International Initiative, Jannike Falk-Anderssons of the Norwegian Institute for Water Research, and Johanna Heymans of the European Marine Board.